Translate

Translate

-

* News

- - Agira 2018, 75 years later

- - Agira 2013, 70 years later

- - Gallery of ceremony 2013

- - Operation Husky 2013

- * Students' Contribute

- * About Us

- * Visitor's Book

- * Collaborators

- * Canadian Battles

- * Italian Defensive Positions

- * Allied Forces

- * Historical Movies

- Historical Information

- Historical Maps

- * Bibliography

- Biographies

- * Catania War Cemetery

- * Moro River War Cemetery

- * Syracuse War Cemetery

At 10am on 30th July 2013 the most moving ceremony commenced at the Canadian Cemetery in Agira.

At 10am on 30th July 2013 the most moving ceremony commenced at the Canadian Cemetery in Agira.

The dead soldiers overlook a beautiful valley with lake "Pozzillo".

About 700 people attended this remembrance including members of the Italian and Canadian armed forces.

The ceremony ended with a person standing at each of the graves and answering the name as the roll call was given.

It took about 20 minutes to go through the list of the dead. It was such a sad and moving event.

Most people was crying. The Seaforth band were present and most were able to stand in front of a Seaforth grave.

At about 10pm after numerous speeches the Seaforth Pipes and Drums entered Garibaldi square to the peal of church bells and to the recorded voice of Peter Stursberg. They played the traditional Retreat in front of a huge crowd. It was a great ending to the day.

The Sicilian adventure “Operation Husky 2013” ended with the opening of the Canadian exhibit at the Catania Museum on July 31, 2013.

The amphibious invasion of Sicily that launched the Italian Campaign, reopened Mediterranean seaways for the Allies, which led to the toppling of Benito Mussolini and marked the beginning of the end for the Nazis on July 10, 1943.

It also served as a dress rehearsal for D-Day, which without the logistical and strategic lessons learned in Sicily would have been much more bloody.

The symbolic 400-kilometre march begun after the unveiling of a new Canadian war memorial dedicated to the 25,000 Canadians who landed on the beaches near Pachino that day.

More than 300,000 Allied troops took part from start to finish. About the same number of Canadians died during the 28 days of fighting of Operation Husky as did during the entire 18 months of the Korean War, 562 in all.

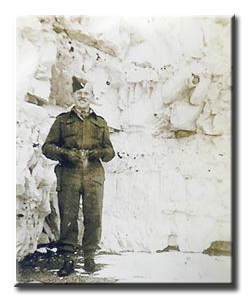

Seven decades haven’t dulled Captain (ret’d) Sherry Atkinson’s memory in the slightest.

Seven decades haven’t dulled Captain (ret’d) Sherry Atkinson’s memory in the slightest.

Born in London in 1921, he was recruited to the Canadian Armed Forces from his job in a department store in Chatham at the age of 17.

At 91, Atkinson is grateful for the chance to return.

“I’m thankful that the conditions are such that I can go back and pay homage to those people once more.”

During his visits to Italy, Captain Sherry Atkinson’s has visited the cemeteries where Canadian soldiers lay. In Agira he has visited the grave of one man he knew during the war, whom he calls “Squeak.”

It’s something that gives Atkinson a measure of comfort, even the better part of a century later.

He has an album of photos and newspaper clippings from his time in Sicily and the years thereafter.

“I got a nice Berretta out of this guy,” he said, smiling and pointing to a photo of a line of Germans his platoon captured. “I smuggled it all the way home and got it registered.”

The battle lasted until Aug. 17, but Atkinson only saw a sliver of it. A lieutenant second-in-command of an anti-tank unit at the time, his war ended just outside of the town of Nissoria.

Two weeks into the invasion of Sicily, his unit of about 50 men was moving north toward the small town when the front line stalled. Intelligence had reported Nissoria was held with a “light” contingent of Axis forces.

“Well guess what” Atkinson said, telling the story slowly and thoughtfully. “The intelligence was wrong.”

The Germans had reinforced within the village, which stymied the Allied advance.

With no choice but to improvise, Atkinson spotted an olive grove that would give his troops cover from the German mortars and heavy 88-inch artillery, and ordered them and the trucks hauling his five anti-tank guns into cover.

What he didn’t know was a recon unit had already come to the same conclusion, and that the Germans saw them moving into the trees.

Atkinson moved his boys into what he thought was effective cover.

It wasn’t.

It wasn’t.

The Axis’ heavy gunners had already “ranged” the olive grove, firing shots behind and in front of the soldiers so they could judge exactly where to drop their artillery for maximum effect.

Within 15 minutes of his ordering the men to dig in, the “sky opened up.”

“They blasted the hell out of us without any warning at all,” he said. “Limbs were blown off trees, explosions were everywhere. It was not very pleasant.”

Since his duty was to make sure the men underneath him were safe, he didn’t have time to dig in himself. With carnage all around him, he dove behind a wrecked tank in search of some protection. It almost worked.

Just as the brunt of the assault had passed, the Germans dropped an 88 round just around the corner of the tank Atkinson was hiding behind. His right shoulder was destroyed by shrapnel no sooner than he was on his feet.

A piece of shrapnel that fit in his hand ended Atkinson’s war on July 24, 1943, the same day the commander of the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR), Lt-Col. Ralph Crowe was killed. The next few months were foggy for him as he travelled mainly by rail between hospitals in northern Africa, including the 1st Canadian hospital in Algeria then back to Britain and another month in hospital later, back to Canada’s London.

He worked for the Department of Pensions and National Health, the precursor to Veterans Affairs Canada for about 30 years, retiring in 1974.

Operation Husky 2013 is being organized by Steve Gregory, a civilian with no official connection to the Canadian military.

Operation Husky 2013 is being organized by Steve Gregory, a civilian with no official connection to the Canadian military.

One of the ways he is fundraising was by selling memorial posts for $150.

The posts are white and emblazoned with a maple leaf. Each has a plaque with the name of a soldier killed during Operation Husky, the place and date they fell.

The posts were placed as close as possible to where they were killed.

“I even bought one for Squeak” , Captain Atkinson said.